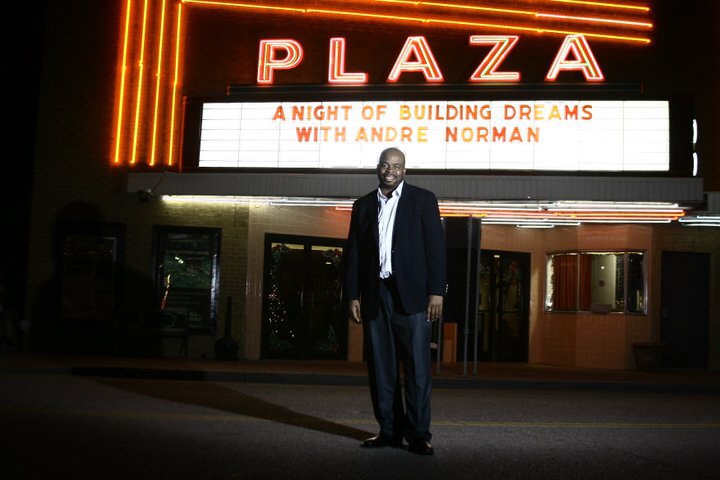

When I first swapped contact info with Andre Norman, he happily informed me that he was on a family Disney cruise. Seconds later, he sent along a selfie to further prove the point. On my phone, I saw the relaxed stranger in his cabin: comfortably stretched out on a couch while casually throwing me a peace sign. Just over his shoulder was a bright green rectangle of ocean. I was momentarily confused. Even though he’s widely referred to as “The Ambassador of Hope,” it still wasn’t quite the Andre Norman I’d expected. Despite knowing that Norman is a sought-after inspirational speaker, it was somewhat impossible to ignore a biography riddled with abuse, crime, gang violence and a decades-long prison sentence in a maximum security prison. “Family Disney Cruise” simply wasn’t a phrase I’d prepared myself for.

It’s not Norman’s past, however, that fascinates and motivates people. Neither is it his decision to transform a deliberately dead-end life into something truly remarkable, either. It’s because Andre Norman is constantly looking ahead with an unparalleled eagerness and optimism. He doesn’t simply believe tomorrow will be brighter than today—he’s absolutely convinced that it will be. That’s the message Norman tirelessly carries all over the world, including far-flung locations like Trinidad and Liberia. He also lectures on topics such as families in crisis, leadership, addiction and prison re-entry, among others. No matter how desperate circumstances may seem, Norman argues, there’s always hope. In many ways, his Disney Cruise selfie underscores that very fact. Absolutely anything is possible—and Andre Norman is determined to prove it to you.

PAUL FUHR: You had a two-year stay in solitary confinement, where you had an “epiphany” to turn your life around. Could you describe what that epiphany actually was?

ANDRE NORMAN: It had to do with God. I was going to stab some people. But suddenly there was God. I’m like, “Why are you bothering me now when you’ve never been around before? Why are you here now?” But I decided not to stab anybody. I went back to my cell. I thought, “What am I going to do now?” All along, I’d wanted to go to Harvard and everybody thought I was crazy. But I got my GED and taught myself the law. I got out [of prison] in 14 years instead of 28. I eventually worked at Harvard.

PF: That’s amazing. Why the goal of Harvard?

AN: Well, my father told me: “No, you can’t do it. You have your place in life: you’re a criminal. And not only is this your place, but you’re really good at it.” (Laughs) “You’re really good at being a criminal. A really, really good inmate.” It’s an individual choice to be what we are. You can change the choices, but some people are so far down the line that they don’t have the strength, drive or determination to do anything else. They’ve accepted it. They’re trapped in the life that they’ve built, whether it’s a prison, a company, a family, or a lifestyle. It’s so much easier to stay.

PF: You’ve said before that you decided to become the toughest person in prison. You actually made a conscious decision to do that. Since you just mentioned being really good at being a prisoner, when did you start realizing that you’re really good at these other things, like public speaking and inspiring others?

AN: If I’m going to be in something, I want to be in charge. I don’t like people making decisions for me. People made decisions for me all my life and they were always bad. In prison, when somebody died, we’d have a memorial service and people would always go: “Dre, say something.” So I’d say some words and end it with a prayer. That happened three or four times a year. I became the de facto pastor for memorial services. We’d also have annual events for Black History Month. We’d bring in choirs, singers, actresses, speakers, whatever. Someone had to emcee those events.

Emceeing wasn’t easy because, with all of those outside people, the emcee represented [everyone in] the prison. And then you’ve got 800 guys and someone’s going to be upset or feel offended by something you said or did. They’d get trashed, absolutely crushed, after the event was over. No one wanted that job. Well, they ran out of emcees one day so they asked me to do it. I’d never spoke in front of that many people before. I kept doing it. What really got me going, though, was this program that brought kids in from the juvenile detention center to the prison. There’d be six prisoners and one volunteer and we’d all sit in a room and just talk.

PF: And that was the big moment for you?

AN: Yeah. Everyone in the youth program asked me to come see them once I got out. They said, “Most people say they’ll come see us, but they never do.” So when I got out, I showed up at the youth center and I went there, every day, for four hours. I went there to talk, to tell them some stories and to tell them what little bit of success I’ve had. Two or three hour speeches at a time. Kids are a tough crowd, too. (Laughs)

PF: Do you enjoy working with a particular demographic or specific age group over others?

AN: I’ll go from kindergarten to grad school. Little kids just want to be picked up. They need energy. You can speak their language. They don’t know the difference between 25 and 40. They just know whether you’re funny or you’re not. I teach them to ask for help; I teach them to say thank you.

PF: What’s your approach, then, with high schoolers?

AN: In high school, you’re going to be forced to make decisions about sex, about gangs, about drugs. You might be dealing with a parent not being present or somebody being in jail. I tell them that they have to get a dream and to hell with everything else. You ride that dream. I tell them that they’re making a choice right now. I ask how many people have an uncle who sleeps on the couch. Everybody’s hands go up. I ask everyone if they want to be the uncle who sleeps on the couch or the cousin who owns the house. Everyone wants to be the person who owns the house.

PF: Since you’ve started your speaking career, what changes or trends have you noticed among the kids you work with?

AN: The trends are among the parents. Not the kids. It used to be that you had to talk to your kids, but now you don’t have to. You can give your kids technology and walk away. We complain as adults that our kids never put their phones down. Well, you give a kid an iPad at age two and he plays with it every day, all day, and then at sixteen, you want to snatch it from him, it doesn’t work like that. Parents can check out now. Parents are disconnected and the kids are like, “Okay, Mom and Dad are checked out, so let me check out.” When I was young, parents talked to you every damn day. They waited to unload on you. (Laughs)

PF: What’s the most rewarding thing about what you do? What keeps you going?

AN: I get to do for people what I’d always wanted done for me. I’ve worked at Harvard, I’ve worked at London Business School, I’ve worked at the White House, I’ve worked with prime ministers, I’ve worked with presidents, I’ve spoken with top CEOs around the world. But what could I have been if someone had grabbed me in second grade and said, “We’re going to teach this kid how to read and write correctly, how to comprehend, and how to be kind.” What could I have been if I someone had raised me correctly, if someone told me that I didn’t have to beg for food, didn’t have to rob people, didn’t have to fight to get into school?

PF: You’re such a strong, commanding presence that it’s hard to imagine you might actually have day-to-day challenges. What challenges do you encounter?

AN: When the people that I’m going to visit don’t believe I’m the guy who should be coming. For example, I went to St. Louis to this private Catholic school for boys. All the fathers and sons go to this annual event. They listen to the speaker, they clap, and they go home. They decided to bring me in. The year before, it was the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals. The fathers are like, “Wait a minute. We’re all Catholic and St. Louis is a Catholic town. Why is a blank gang member coming in to talk to our kids? Our kids aren’t going to be gang members and they’re definitely not going to be black.” Most speakers come out and do their 40 minutes of speaking, then leave. I showed up and arranged for all the boys to come into another room and I spoke to them for like 45 minutes beforehand. Then I got on stage and did the whole group. After it was over, one of the fathers came up to me and apologized. He said he was one of the biggest advocates against me to speak. It made no sense to him. He read my bio and I didn’t make any sense. But the father said, “I don’t know what you said to my kid in that other room, but he came out a different kid.” Many times, though, I’ll be trying to help someone’s kid and their parents will have all of these questions and doubts about me while their kid suffers.

PF: Well, that ties back to your original comment about parents being half the problem, right?

AN: 80% of the problem. And not in the sense that they’re giving their kids drugs. But if you’re not in the conversation and you’re not paying attention, it can get away from you fast.

PF: With all that you’re doing to give back to others, do you ever stop to appreciate just how far you’ve come in life?

AN: Look, I was the boss in the penitentiary. Not kinda-sorta or halfway. Full-fledged. I know that life and I can go back to that life. But what I do now is who I am. I just want to help somebody. I’m not asking you to put me on your mortgage or to give me the keys to your car. Let me help you. Stop judging. I don’t need you to like me. I don’t need you to want me to live long. I just need to live long enough to help you or your kid.